20 December 2018

It is 10 years since the introduction of the first human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination programmes in Europe. At an anniversary conference in Portugal in November, Adam Finn, Professor of Paediatrics and research lead for Developing Microbiology and Population Studies at the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol, highlighted the successes, challenges, and striking variations in vaccination coverage among target populations across individual countries.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection and a major cause of cancer. Overall, HPV causes 1 in 20 of all cancers, and 1 in 7 cancers in women worldwide. Nearly all cervical cancers are caused by HPV. In Europe, there are 33,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 15,000 deaths from cervical cancer each year. The number of cases of oral cancer (mouth and throat) caused by HPV, especially in men, is rising.

HPV also causes genital warts. In Europe, around 7.5 million people have genital warts.

HPV vaccines prevent infection by protecting individuals and by preventing those individuals from passing the virus on to others. HPV vaccination programmes can therefore “protect everybody”. Vaccination is usually targeted at young people (mainly girls) aged 12-13 before they become sexually active. In the UK the programme will also be rolled out to boys in 2019.

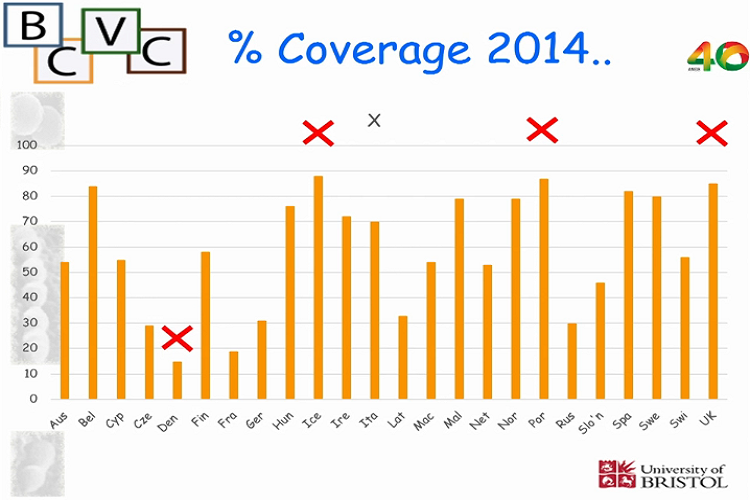

Despite most Western European countries adopting HPV vaccination programmes since the vaccines were first licensed in 2006, there is still large variation in the percentage of the target population covered – from around 15% in Denmark (a low point) to almost 90% in Iceland and Portugal since 2014. For maximal impact, coverage needs to be sustained at the highest levels possible, ideally above 85%.

A ‘vaccine scare’ in Denmark seriously affected uptake, the impact of which, because of the length of time it takes HPV-related cancer to develop, will not be fully felt for many years to come.

In the UK, which has around 86% coverage, there is evidence of a halving of cancer-causing HPV prevalence in young people in the two to three years after vaccination, and a further halving in the two to three years following that, down to a detection rate of 4%.

“One of the biggest challenges for the future, in all countries, no matter how effective their vaccination programmes have been”, says Professor Finn, “is communication. Because it only takes the emergence of a false narrative, as occurred in Denmark, to be amplified, repeated and taken on board, to have a collapse in public confidence and trust. We need to think about ways that we can communicate, not to the converted, but other people who don’t really know about vaccination. How do we make sure they understand enough to be robust against those false stories?”

Watch Professor Finn’s presentation (Vimeo) (Length: 18:52).

Professor Finn was invited to speak at the event to commemorate the 10th anniversary of HPV vaccination in Portugal, organised by the General Directorate of Health of the Portuguese Government on 5 November 2018 which concluded with an address from the President of the Republic.